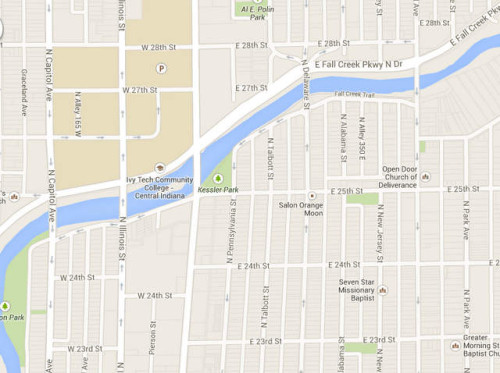

The urban advocates are nearly unanimous that our metro areas, in general, suffer from a dearth of good urban park space. Nonetheless, it is often hard to build much of an argument for new park construction, or the requisite land assembly. After all, most American cities are seriously lacking when it comes to density, and it doesn’t take much for us to think of a park in [insert your city here] that is practically always deserted. While Indy holds up fairly well in court of public opinion when it comes to our downtown park and civic space, the rest of the city isn’t exactly winning any awards. A good case in point is a near northside park that many readers probably never knew existed: Kessler Park, wedged between Fall Creek and the respective neighborhood of Fall Creek Place.

It should come as no surprise that this park is a relative newcomer to the city’s system. It and a few other green spaces (such as the one at 25th and New Jersey, or its counterpart two blocks south) owe their existence to the site planning that took place approximately 15 years ago, with the development of Fall Creek Place in what had been one of the city’s most derelict and abandoned neighborhoods. One might presume that the individuals who conceived Kessler Park saw its potential as a focal point for the neighborhood. After all, they named it after George Kessler, celebrated landscape architect and second only to the Olmsted pére et fils in terms of his contributions toward the design of urban parklands. While Kessler’s best-regarded system remains Kansas City’s extensive park network, he also laid the cornerstone for Indianapolis’ “green velvet gloveâ€: the waterways of Pogue’s Run, Fall Creek, Eagle Creek, and White River all achieved far greater levels of protection through his parkway system than they otherwise would have enjoyed. He also expanded the layout of Garfield Park, designing the sinuous streets, the sunken gardens, and the conservatory. Incidentally, Kessler died in Indianapolis while surveying during the construction of another prominent road; the city’s most confusing street, Kessler Boulevard, honors the man.

Kessler Boulevard is unquestionably a higher-profile tribute than this pocket park, which I suspect measures somewhere between one and two acres.

Indy Parks has diligently maintained it; as far as its physical appearance is concerned, it would be hard not to consider it an amenity to Fall Creek Place. And yet, the general reputation—at least according to a fellow Urban Indy writer who visits the park far more than I do—is that Kessler Park is nearly always completely empty. What seems to be the problem? Is it the surrounding neighborhood simply insufficiently dense to support a park?

Not likely to be the case. Though predominantly a neighborhood of single-family houses, Fall Creek Place certainly follows an urban typology in terms of lot size and alleys in the back. The corners to certain blocks include townhomes at a higher density, and, directly to the north of the park on the other side of Fall Creek, sit two other prominent nodes: the popular Marott apartment building and the campus of Ivy Tech.

Granted, these features come with many disclaimers. Fall Creek Place is only a dense urban neighborhood by Indianapolis standards—it is hardly as dense as many neighborhoods in Chicago, Minneapolis, or Columbus Ohio, for that matter. And Ivy Tech, at this point, remains primarily a commuter school, so it doesn’t generate a great deal of pedestrian traffic in the evenings. Meanwhile, the Marott Apartments, though popular, sit perched along Meridian Street and Fall Creek like a citadel, completely gated off from the urban environment, which until recent years no doubt was fairly threatening. So, in truth, the human concentration in the area is only modest and clearly not enough to stimulate many visitors.

The physical layout and site design of Kessler Park revals both assets and drawbacks. At the very least, the Fall Creek Greenway transects the park, meaning joggers and bicyclists using the trail cannot really avoid it.

At the time of this blog post, however, the Fall Creek Greenway is far from complete, and this segment in the park offers little more than a fragment—not a means of getting anywhere in particular. In the future, when it links IUPUI campus to Ivy Tech and the northeast suburbs, it could become a prominent arterial for non-vehicular traffic. At the very least, this stretch of pavement has more to offer than the other one within the park’s perimeter: a small off-street lot for three cars.

What a shame. The installation of these spaces—just as unused as the park itself—bespeaks Indy’s overwhelmingly auto-oriented mentality. Kessler Park is urban and neighborhood-oriented, so why on earth does it need to sacrifice approximately one-fifth of its acreage for cars? After all, vehicles could just as easily park on the street, just a few feet away.

Still, I’m not convinced that these superfluous parking spaces are hurting the park any more than the greenway segment is helping it. In the end, Kessler Park’s deficiency may come down to programming.

The inclusion of this pocket park in the site plan for Fall Creek Place embodies an intention in search of an idea. Clearly a green space, in theory, should serve as a neighborhood amenity, as long as it stays maintained. But, beyond the notion that a pocket park along Fall Creek is a good idea, did the designers really think it through? The homes of the area are reasonably close together—by suburban standards—but not so jam packed that they don’t have yards. For most families choosing to live in Fall Creek Place, a 1/6 acre lot is more than enough for kids to romp around. They’re even big enough for a swing set. What, therefore, could possibly distinguish Kessler Park? Perhaps a playground of its own—right where those #*$(@ parking spaces are right now—would give the park a reason for being. Maybe instead it needs something out of the ordinary: a place for bocce, hurling, jarts or some other yuppie fad. Maybe all it takes is an ambitious go-getter to schedule flash-mob tai chi or zumba. At any rate, Kessler Park remains devoid of stimulation at the moment, and, barring a radical change to either the park or the neighborhood’s density, I see nothing likely to change in the near future.

Although Kessler Park is likely to languish without some serious reconsideration of its purpose, I never want to insinuate that such green space will never succeed on its own terms, nor is programming a panacea. Far too often, planners and designers have conceived of urban parks as destinations that absolutely must boast a certain degree of magnetism in order to be viable, so they jam them with amenities. Case in point: my current home in Detroit. Campus Martius Park, right in the heart of the Motor City’s downtown, is probably not much bigger than Indy’s Kessler Park, but it remains a centerpiece. I took the photos below during the free Detroit Jazz Fest, so they deceive in terms of the crowds, but even on an off-peak afternoon, Campus Martius is almost definitely the most buzzing space in downtown Detroit.

The central lawn features chairs that, at any given time, could all point directly to the stage, which during favorable weather hosts live music or movie screenings at night.

This time, they’re pointing in the direction of the adjacent plaza Cadillac Square, home of Jazz Fest’s main stage.

But that’s not all. The park hosts a restaurant, the popular Fountain Bistro, with indoor and abundant outdoor seating.

The southern half of the park features a huge fountain, which “erupts†in a lively water display intermittently:

A prominent monument statue at the far southern point:

And, in between the fountain and statue, the park’s most winsome feature: a mini beach and temporary cabana bar.

In the winter, this beach converts to a skating rink.

With so much going on, it’s hard to believe the park only occupies a little over an acre. (It’s not so hard to believe that it was a traffic circle from the 1930s until 2004, when the business community pooled its resources and re-established the park as a gift to the financially-strapped city—but that’s another story.) At any rate, it’s easy to see why locals have referred to it as Detroit’s Gathering Place. How couldn’t it be? The planners programmed every square inch of it. But it’s hard not to summon a little pessimism whenever I hear what a great public space Campus Martius is. After all, it does generally succeed in attracting people more than any other outdoor locale in this beleaguered city’s downtown. But flies tend toward the honey, and preschoolers crowd around the cookie jar. I remain unconvinced that Campus Martius would attract many visitors if its conceivers hadn’t transformed so much of it into commercialized event space. After all, the city’s handsome but antiseptic Hart Plaza boasts marvelous views of the international waterfront with Windsor Canada, but you’d be hard pressed to see more people lingering in Hart Plaza than you have fingers on one hand—unless a special event is taking place.

Detroit needed a centerpiece jammed with destination-type activities in order to convince people to visit, and that’s precisely what it got. Campus Martius is a successful park, but it cynically and naively operates by transposing Keynsian economic principles to the collective human will: if you prime the pump enough, you’ll get the desired results. To put it even more glibly (sorry Field of Dreams fans): build it and they will come. The park’s designers don’t trust that Detroiters will engage the space voluntarily; they cynically determined that the park must entice the public, then tell them how they will use the space. To be fair, these designers may very well have been correct in their assumptions. If the park’s creative team hadn’t stuffed the park with commercialized goodies, would it ever be that much busier than Indy’s Kessler Park? Or all the other lifeless plazas across numerous American downtowns?

Lest I confuse my readers with where I’m going with this strange analogy, I will admit that I recognize what Campus Martius Park has achieved for America’s most economically devastated major city. And Campus Martius has a lot at stake, right in the heart of its city’s downtown.  But I don’t admire Campus Martius. I find it disingenuous to call it a great public space, anymore that we’d say that about the amusement rides at a state fairgrounds, or even Disneyland.

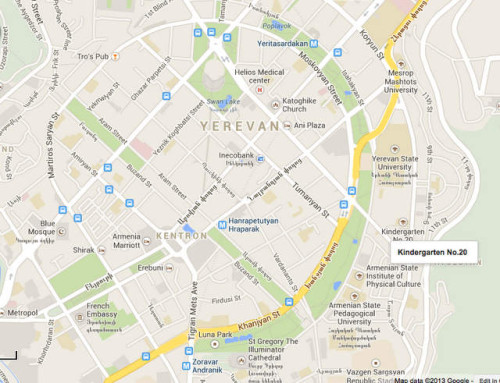

In the end, despite its overstuffed qualities, Campus Martius reflects a paucity of thinking rather than any excess. As a final example of where poorly conceived programming is the equivalent of etiolating, I present an example way out on left field: Yerevan, the capital of Armenia.

It doesn’t take a brain surgeon to figure out that central Yerevan’s layout didn’t exactly emerge organically. Any map will get the point across.

Yes, the almost 3,000-year-old city is one of the most rigidly designed municipalities in all of southwest Asia—a product of the Soviets, who hired architect Alexander Tamanian to construct the ribbon park that encircles a conventional grid. In the interest of providing adequate green space for the city of 150,000 the “General Plan of Yerevan†necessitated the bulldozing of hundreds of ancient buildings. The typical visitor to Yerevan today would hardly be able to guess the city’s Biblical origins.

While Tamanian’s General Plan pulverized the city’s architectural legacy, in recent years his own parklike vision has suffered undue compromise.

Informal vendors clog many of the civic plazas, selling knickknacks to tourists through temporary stalls.

I’d have to be a real Ebenezer to begrudge people this means of making a living, especially considering that the stalls are easy to dismantle and remove if necessary. But what about the more permanent installations?

These pictures only skim the surface of what is going on in central Yerevan’s circular park ribbon. The truth is, the entire park is glutted with restaurants, cafes, and permanent concession stands. I’ll concede that the final of these photos suggests a charming lakeside nook, and it’s certainly nice looking. But restaurant owners clearly thought the same thing, and whatever the permitting process might be in Armenia, the City of Yerevan sold out the majority of the open space. The result is linear park that is too congested with tables, chairs, booths, and cafés to allow for jogging, bicycling, or much of anything. When you’re in the midst of the park, it feels closer to King’s Island than anything. Not surprisingly, even corporate America has struck a claim on the space; the park was the only place in all of Armenia where I saw a national restaurant chain. (It was KFC, though, since my visit, McDonald’s has entered the Armenian market.) The commercialization of Yerevan’s park space seems all the more ironic when one realizes that, just two decades earlier, the country was a state in the USSR, completely closed off from Western influence and rigidly enforcing state ownership of all urban lands. Now the park sells Kentucky Fried Chicken seven days a week.

Obviously I have had to apply some real rhetorical gymnastics to shoehorn this comparison of park spaces in Indianapolis, Detroit, and Yerevan (!)—not only are they vastly different cities with parks of differing sizes, but they all rest on different sites in relation to their respective central business districts. The one critical similarity is that they all demonstrate weaknesses in the treatment of programming. While Detroit’s Campus Martius remains generally lively against all odds, it doesn’t ever seem to serve as “the lungs of the cityâ€â€”it’s way too crammed with blandishments to feel like much of a respite. Yerevan’s Circular Park expands upon the mentality of Campus Martius across hundreds more acres. Though it doesn’t appear as aggressively master planned, it betrays the same cynicism as in Detroit, since it operates under the mentality that people need commercial attractions as an incentive to use their green space. (A strange notion, since the vast majority of Armenians live in attached or multifamily buildings without individual gardens or yards.) Then Indy’s Kessler Park takes the most laissez faire approach, erroneously assuming that moderate density will be enough to populate the park organically, which clearly isn’t the case. I don’t think anyone expects this park to turn into a centerpiece for all of Indianapolis, but even a greater sensitivity the recreational goals of the Fall Creek Place neighborhood could earn the pocket park a little bit more use. The neighbors might even get to know that it exists.

I was thinking about the lack of activity in some of our downtown spaces this weekend as I sat in Bryant Park in NYC watching people play ping pong on outdoor tables, enjoy free reading materials in an outdoor “reading room,” or grab a bit from the meal kiosks at the park’s edge. Dozens of outdoor tables were full and people were sunning themselves and playing Frisbee in the open grounds.

I was going to point out that the better Indianapolis analog to Campus Martius might be be either Military Park or the Legion Mall/University Park. Or even the Circle.

I’d also point out that there is an even bigger (6 acres) and even more underutilized park just three blocks west of Kessler Park: Barton Park, which has some really cool streambank and riverine features. It also has a playground and picnic tables.

And do I detect a bit of disdain for the PPS penchant for programming public space?

—

With specific regard to Kessler Park, it’s not an easy walk from Ivy Tech (major understatement). It’s also not a practical part of a walking loop from the Marott Apartments because one cannot cross Fall Creek Parkway N. Dr. at Delaware St. on foot. And it’s parked in the NW corner of Fall Creek Place, in the strip between Penn and Meridian that is almost all commercial in the block between 23rd and 24th. Only a handful of houses front on it.

I think at this juncture, it’s a bit like Alice Carter Park (at Meridian and Westfield) used to be: just a big greenspace at a prominent intersection that everyone can see, near but not really in neighborhoods. Now that it is better connected to Meridian Kessler and Butler Tarkington neighborhoods, there are a few more people using it.

But it is still really just space left over in plan, what architects abbreviate jokingly as SLOP.

The homes of [Fall Creek Place] are reasonably close together—by suburban standards—but not so jam packed that they don’t have yards.

This is the essential issue with all the parks in FCP: not one of them differentiates itself from my back yard. I take my daughter to the neighborhood parks because they’re there and I feel like I should use them, not because they offer something interesting and unusual.

Some of the park non-use could be blamed on the master plan of FCP. There are several areas of the neighborhood that hindsight would say should have had a different layout. 22nd arguably should have had no directly adjacent houses. That land could have been reserved for small mixed-use buildings, or at the very least 2-4 story apartments.

The properties surrounding ALL the parks likewise should have been reserved for higher-density residential. A single family house directly adjacent to a park generally considers a lot of “hubbub” in the park to be a nuisance. To an apartment building, hubbub at the park next door is just part of life because the residents must share many things, including the public green space next door.

This is the essential issue with all the parks in FCP: not one of them differentiates itself from my back yard.

And this is a much bigger statement than you intended to make.

I have always thought, but never really argued, that at Indianapolis’ density level, there is PLENTY of green space in the city for playsets and Frisbee and pools and sandboxes and football.

I have to admit that this is why I dismiss the “we don’t have enough parks” rankings: we all have private parks next to our houses.

And this may be why your neighborhood parks don’t feel different from your back yard…they may not be!

Just some minor things to point out about Kessler park.

1. The park originally held the offices for the redevelopment of Fall Creek Place and the small off street parking spaces were primarily used for that purpose.

2. The park does get use as an open space. Mostly by residents playing with their pets, catch, or frisbee.

3. I have seen far more activity at that park than either of the two ‘pocket’ parks, in the neighborhood. The other two pocket parks were originally designed bo be open space surrounded by townhomes. The townhomes would have had very little yard space, therefore, the parks would make sense. Somewhere along the line, it was decided to remove the townhomes, and keep the traditional single-family detached.

4. I believe the parks are maintained by the homeowners association, not the parks department. Just as the ornamental street lights are paid by the homeowners association, not the city.

5. A portion of the space that is now underutilized green space, used to be a road. I’d take the green space over an empty road any day.

Is it under utlized? Definitely. But there are far worse under utilized spaces in Indy than this one.

The other pocket parks in FCP are in fact owned and maintained by the HOA – and, maintained quite well. Kessler Park is not – it is owned by the city and “maintained” by the city. As a resident of FCP, I love the greenspace that these parks provide (even the sporadic maintenance of Kessler Park is better than that in most city parks), and our family does in fact use them – primarily for playing with our dogs, flying kites, letting the kids run around, etc.

The pocket parks in FCP (including Kessler Park) are fairly small spaces, and wouldn’t be amenable to much greater use than what they are used for now: being a pretty bit of green space. Once the connecting bike trails are completed however, I would love to see Kessler become a kind of cycling hub/terminus for connections to the Monon and beyond.

Thanks as always for the comments. I’m aware that the Kessler/Campus Martius analogy is a bit strange, but it really had to do with parks that represent too opposite extremes in terms of programming. And yes, I’d agree that Kessler comes dangerously close to feeling like SLOP. I was not aware of the magnitude of awful connectivity between the north side of Fall Creek and the south side (I thought it was simply not good, rather than terrible). Not that it probably matters, since even with good connectivity, most Ivy Tech students or Marott dwellers aren’t going to be particularly cognizant of Kessler Park.

Chris Barnett, my disdain for park programming is less about the practice–after all, it’s likely that Kessler Park could benefit from some programming. However, it often appears that park planners go the opposite extreme and depend exclusively on programming to attract visitors, as seems to be the case with Campus Martius. While I understand your argument about density and park spaces, I still feel like it’s not an entirely satisfying excuse for the weak park system in Indy. It’s not so much that Indy lacks green space, but many other cities also are dominated by single-family houses with yards and yet still have robust park systems. Kansas City comes to mind, as referenced in this blog article. Granted, Kansas City also probably has more unused parkland than Indy, since it’s an even lower-density city. But if Indy could even reclaim Fall Creek/Pogue’s Run/White River under Kessler’s original plan, making them dedicated park space through the greenway network, we’d have a functional system, rather than a bunch of unmaintained creekside land that hardly anyone knows was originally intended to serve as a park.